The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

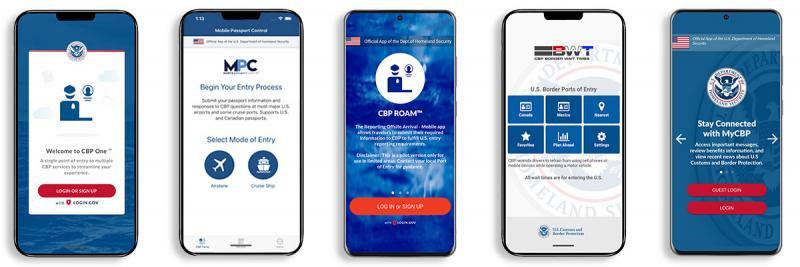

How the CBP One App Fails Asylum-Seekers

By on June 9, 2023

The rights of those seeking asylum are frequently under attack. If not by blatant xenophobia and racism, then by red tape and bureaucratic policies serving to hinder asylum-seekers from obtaining their legal rights. Often, the latter is the result of the former.

The CBP One app sits in this unfortunate category. UUSC joins the growing number of human rights groups in condemning the CBP One app and its impeding asylum-seekers’ rights. The app is—and has been—a focal point of the Biden administration’s border policies in the months leading up to the termination of the controversial and regressive Title 42 policy. U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) is housed under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and is the primary agency responsible for securing the border and processing those seeking asylum and refuge at legal ports of entry.

When CBP One first came online in January of this year, users accessed the app to request Title 42 exemptions and schedule appointments at ports of entry. Asylum-seekers from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela were specifically told to request appointments through the app. CBP One’s purpose was to replace the previous system where civil society organizations recommended individuals to apply for legal immigration status with CBP, which led to massive corruption and exploitation of those seeking safety.

This smartphone application underwent a major overhaul at the same time that Title 42—the public health policy revived and weaponized by the Trump Administration in 2020 to block asylum-seekers from entering the country—ended. The hope was to eliminate the issues with the app and the application process itself. Unfortunately, things have only gotten worse. Instead of making the app easier to use, the latest update made it even more challenging. Users report receiving error messages, long loading times, and crashes due to the large number of individuals logging on to the app. Also, as many have pointed out, a system that requires peak smartphone operation and internet access further restricts those without those resources, particularly those in transit through Central and South America.

App users are also reporting language barriers that further complicate the process. While there are parts of the app that are translated into English, Spanish, Russian, Portuguese, and Haitian Creole, the most important parts of the app are primarily in English and Spanish.

“We were seeing that lots of people who don’t speak either Spanish or English are paying other people to apply for them,” said Jean Jeef Nelson, a case manager in San Diego and Tijuana for UUSC partner Haitian Bridge Alliance. “And those who don’t have any money are usually stuck.”

Respond Crisis Translation, a collective of language justice activists in the United States, is working to bridge the gap for those communities whose languages are not represented on CBP One—a failure of the application that the organization is calling “language violence.”

NPR reported on the changes that immigration officials have been implementing to improve access to the app. Among these changes are extending appointment availability and increasing the number of appointments from 750 to 1,000 per day.

“These changes will provide noncitizens with limited connectivity the same opportunity to schedule appointments to present themselves for inspection at Southwest Border ports of entry as those with better internet connections,” reads a portion of a May 5 statement from CBP about the app’s overhaul.

DHS considers CPB One a success with DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas highlighting the aforementioned changes as well as outreach to migrants in the United States and Mexico to seek their feedback on the app. He maintains that the greatest challenge is not the app’s functionality, but “the fact that we have many more migrants than we have capacity to make appointments for.”

However, not all government officials agree. Rep. Julian Castro (D-TX), joined with several other members of Congress to call for improvements to CPB One and the process as a whole.

“We ask that the administration develop alternative pathways to apply for Title 42 exemption appointments immediately, while rapidly disseminating concise and accessible information about both how to use the app and the availability of alternative methods for individuals who do not have access to the application,” says a March 14 joint statement penned by Castro and more than 30 House Democrats.

Human rights organizations have resoundingly disagreed with the administration’s assessment of the app’s success. Nicole Ramos, director of former UUSC partner Al Otro Lado, called CBP One an “unmitigated disaster,” while detailing how many people are still unable to receive appointments and are booted off the app after significant wait times. Ramos claims that scammers are still scheduling appointments and selling them to asylum-seekers, with the sellers canceling their appointment after receiving payment and the buyer taking the open spot.

Amnesty International condemns the app on the grounds that its implementation is a violation of international human rights law. The organization fully details its position in a policy brief. Citing the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the organization notes that the United States is obligated to provide access to, “individualized and fair assessments” for all seeking asylum with methods that are not discriminatory.

While seeking asylum is a federal process, individual states have the jurisdiction to determine their own policies on how to process requests. The fact that a user has to install the app on their phone means state governments would have access to key information markers about them, such as location and country of origin.

As Americas Director Erika Guevara-Rosas notes, requiring the app’s use would allow CBP to “ping” the phones of those in migration, granting them access to all sorts of data from the user’s device. This data could be used to discriminate against people seeing refuge.

UUSC upholds the right to travel freely without undue danger and restriction. Our neighbors from all over the world deserve the right to flourish wherever they are planted, whether they decide to remain rooted in their homelands or replant themselves abroad. We join other human rights organizations in expressing deep concern over the usage and condition of the CBP One app, especially the concern that it infringes upon the rights of asylum-seekers. We call on President Biden to honor his pro-immigration promise and regain the trust of immigrant communities across the United States through shaping and building an equitable immigration process.

Image Credit: US Customs and Border Protection