The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

Reflections on the Honduran Election, One Year Later

By on November 28, 2018

If “[t]he history of Honduras could be written on a rifle, on a gunshot, or rather, inside a drop of blood,” as the Honduran poet Roberto Sosa wrote, then the 2017 presidential election in Honduras is one of the more recent flashpoints in that history. The election, which took place one year ago, was marred by electoral fraud, a violent government crackdown on protesters, and U.S. complicity in human rights violations in the region. Yet, it also served as a fresh reminder of the courage of the citizens of Honduras, for whom the violent crackdown is not an anomaly or aberration, but a lived reality.

There were concerns about the election, even before it began. The incumbent, Juan Orlando Hernandez was the first Honduran president to seek re-election – until 2015 there was a constitutional article that prohibited an incumbent president from seeking re-election. It bears noting that this constitutional article served as the justification for a 2009 coup d’état that removed President Manuel Zelaya from office, who was seeking a referendum on the article. Zelaya’s opponents at the time claimed that he was seeking to change the constitution. The irony is that the subsequent post-coup government has taken aim at these same constitutional term limits in order to remain in power, including by replacing several members of the Honduran supreme court in 2012 with judges more sympathetic to the ruling party.

Although the U.S. initially called the 2009 coup illegal, it worked behind the scenes to prevent Zelaya from returning to power and refused to suspend aid to Honduras, as is required in the wake of a coup. The 2009 coup, and the U.S. response, helped lay the groundwork for the 2017 political crisis.

Once the election was underway, however, the concern shifted to electoral fraud. Opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla led Hernandez by a significant margin with almost 60% of the votes tallied. However, during the count, the electronic voting system went down. Once the system was up-and-running again, it showed that Hernandez was narrowly leading Nasralla.

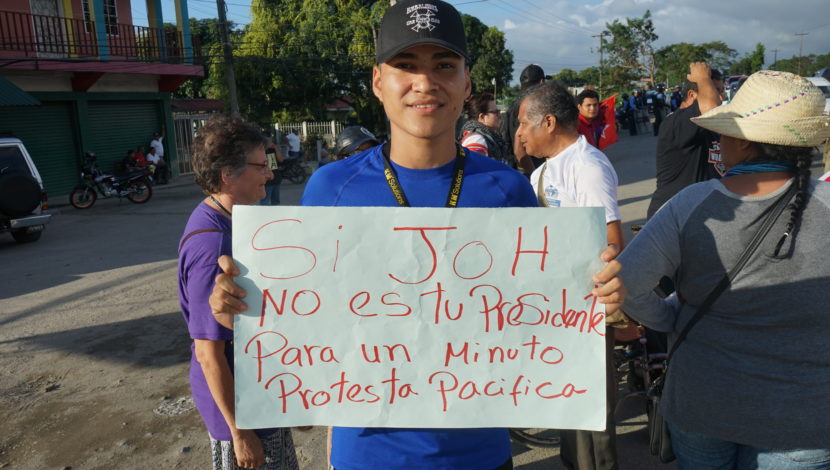

The announcement by the Honduran electoral commission that Hernandez had won the election set off waves of protests across the country. The government’s response was to crack down on the protests, impose a 10-day curfew, and declare a state of emergency. Overall, the crackdown left at least 30 people dead and 60 people injured by Honduran security forces during the protests and resulted in the arrest of over 1,300 people.

As highlighted in UUSC’s recent report, many of those who were arrested for their participation in the protests were rounded up at their homes, often in the early morning in front of their families, and accused of crimes they did not commit. They faced beatings, torture, and threats of extrajudicial execution. Some were placed in solitary confinement and given rat feces and stones to eat.

In many of these human rights violations, the United States was complicit. Several individuals who were detained and tortured identified the TIGRES and COBRAS, Honduran special forces units receiving support and training from the United States. Additionally, despite the initial calls by the Organization of American States for a re-election due to the “poor quality” of the election process and the violent response to the protests, the U.S. State Department certified that the Honduran government was “making progress on improving human rights and tackling widespread corruption” just two days after the election. By late-December 2017, the United States had recognized Hernandez as the winner.

As I prepare to head to Honduras with the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice (UUCSJ) later this week, I will be carrying with me the weight of the history of U.S. policy in Honduras and how it has worsened the human rights situation in the country. Through our responses to the 2009 coup and 2017 elections, and our support for the militarization of Honduras, the United States has helped fuel human rights violations and forced migration.

But, I will also be reflecting on the courage of the protesters, activists, and human rights defenders in Honduras. They, and their families, face death threats, arbitrary detention, and torture in order to defend human rights in Honduras. Their effort to protect human rights is a beacon of hope. I hope to learn from their courage and be in solidarity with their work.

While the 2017 election may in many ways be a reminder that the history of Honduras is written on a rifle, the courage of the Honduran people is a reminder that its future doesn’t have to be.